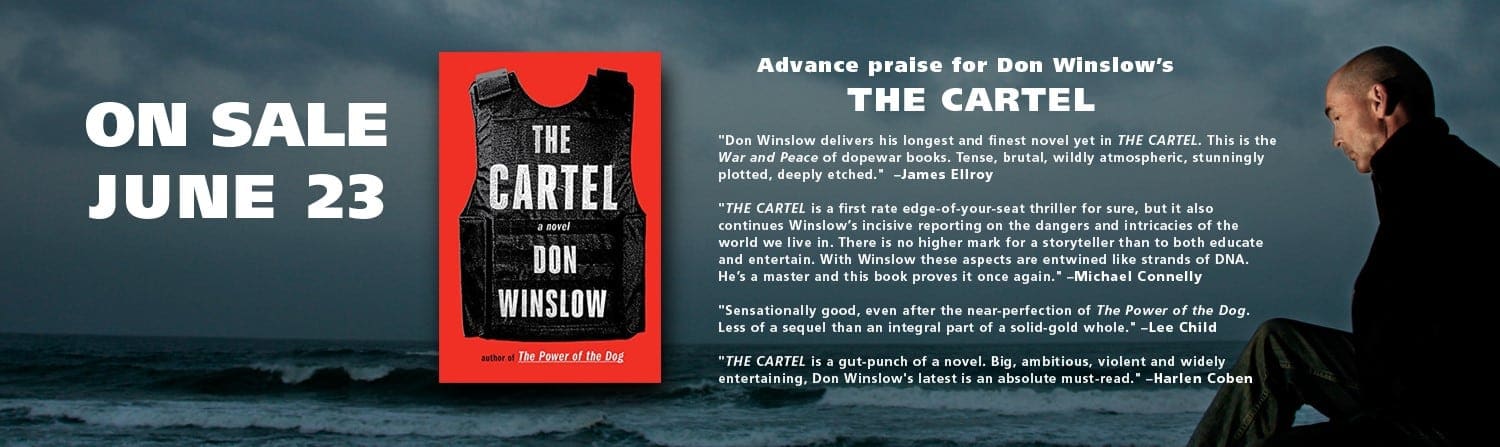

In the June 2015 edition of BookNews, you’ll find signed books for Nelson DeMille, Don, Winslow, Brad Meltzer, Shona Patel, and many more! Click here to view the PDF.

poisonedpeeps

poisonedpeeps

BookNews – Magical, Mysterious, May

In the May 2015 edition of BookNews, you’ll find signed books for Jeffery Deaver, Carolyn G Hart, Stephen Hunter, and many more… Click here to view the PDF.

BookNews – As usual, April showers us with books and authors

In the April 2015 edition of BookNews, you’ll find signed books for Susanna Kearsley, Steve Berry, John Sandford, and many more… Click here to view the PDF.

BookNews – A Marvelous March

In the March 2015 edition of BookNews, you’ll find signed books for CJ Box, Dennis Lehane, Jacqueline Winspear, and many more… Click here to view the PDF.

BookNews – Happy Valentine’s Day to All…

In the February 2015 edition of BookNews, you’ll find signed books by Joanne Fluke, James Rollins, Francine Matthews, and many more … Click here to view the PDF.

Diana Gabaldon and The Poisoned Pen present our first joint Writers in Residence Program Charles Finch February 21-28

Diana Gabaldon and The Poisoned Pen present our first joint Writers in Residence Program

Charles Finch February 21-28

Charles Finch will spend a week in Scottsdale hosting author events (Laurie R. King, Priscilla Royal, Tessa Arlen), do an event for his own work in Peoria February 26 6:30 PM, and teach two Writer’s Workshops: call 480 947 2074 or 888 560 9919 to register.

SUNDAY FEBRUARY 22 2:00-5:00 PM at The Pen

$50. Registration required.Limited to 30 participants

Getting Your Novel Off the Ground

Charles Finch will offer an introduction to getting a novel started – the basic elements of story, character, and planning that are necessary to take a book from your mind to the page. A sample of between 500 and 1200 words, preferably from a first chapter; a one-page synopsis.

SATURDAY FEBRUARY 28 10 AM-1:00 PM

With a follow up from 3:30-4:30 PM after the scheduled author event with Jeffery Deaver and Francine Mathews

$50. Registration required. Limited to 30 participants

Story Structure Masterclass

Drawing on the proven techniques of the novel and the screenplay, this three-hour workshop from author Charles Finch will offer an in-depth examination on the mechanics of storytelling, and how they can improve your novel.

Charles Finch is the bestselling author of the Charles Lenox mystery novels, set in Victorian England and nominated for the Nero and Agatha Awards-the latest is The Laws of Murder(St Martins $25.99)-as well as a standalone literary novel about a group of students at Oxford, The Last Enchantments (St Martins $24.99). He regularly writes about books for The New York Times, Slate, USA Today, and the Chicago Tribune, his hometown newspaper.