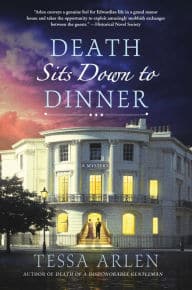

It may seem unusual for The Poisoned Pen to host an author at 2 PM on a Wednesday. But Tessa Arlen will be here for an Afternoon Tea on April 6, and she will also discuss and sign her latest mystery, Death Sits Down to Dinner.

I had the chance to ask Tessa about her Edwardian mysteries. This is a fun interview, split into two days of Q&A.

- Your mystery series is set in the Edwardian period before the Great War. I’m sure you could write a book about the history, but would you give us just a little background about those years? What should readers know?

The Edwardian era spans from 1901 with the coronation of King Edward VII and runs through to the beginning of WW1 in 1914, despite the fact that Edward VII died in 1910 and was succeeded by his son George V. Edward VII or Bertie has he is still affectionately known began his reign at the start of a new and exciting century full of innovation in transportation, communication and manufacturing but also in the arts.

There was a Liberal government hell bent on social reform and taxing the landed classes to provide funds for those reforms. The power of veto in the House of Lords had been broken for the first time in history simply by flooding the house with newly appointed peers of the Liberal persuasion. The age of the motor car and the fast train had contributed severely to suburbanizing the countryside around major cities, and an ever-increasing middle class enjoyed a standard of living unknown in the previous century.

In the coronation year of 1911 when George V succeeded his father as king and emperor the British Empire had already reached its zenith forty years before. It was not the end of Britain’s world power ““but America was already emerging as the next economic world leader and life was still remarkably good for the rich and most of the landed aristocracy. 1911 was one of the hottest summers on record. And it almost seems as if this un-English weather fermented trouble: there was a dock-workers strike that caused havoc throughout the country which spurred on other trade unions to support strike action for better pay and working conditions; the Irish were demanding home rule; the rich had never been richer and the poor more desperate. And on top of that the Women’s Social and Political Union’s (Suffragettes) fight for the franchise under the leadership of the Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters Christabel and Sylvia had turned decidedly nasty. A perfect time in which to writer about murder!

- You have two amateur sleuths in the Lady Montfort series. Would you introduce them, and tell us why you have two?

Clementine Elizabeth Talbot, the Countess of Montfort is a mildly eccentric aristocrat’s wife with a good deal of vitality and a husband who admires her quick and energetic mind. She was brought up in India, the daughter of the Governor of Madras, and married the most eligible bachelor during her first London season. It is possible that her Indian upbringing made her a little less conventional than most women of her time. In 1912 she had just celebrated her fortieth birthday. She is tall with rich bay brown hair and blue eyes.

Mrs. Edith Jackson is Lady Montfort’s housekeeper and holds a very senior position in the Earl of Montfort’s country house, Iyntwood. She is single, housekeepers were given the title Mrs. out of respect even if they were spinsters. She was raised in a parish orphanage and was a working kitchen skivvy at fourteen. She taught herself to read and write and is naturally reserved. Mrs. Jackson is as circumspect as Lady Montfort is outgoing, and even though she can be quite severe she has a well-developed sense of humor and an interesting inner-monologue. She is extremely conscious of her position as senior servant to a family of consequence and is probably a far greater snob than her mistress. Like her mistress she is a tall woman with russet brown hair and large gray eyes, she is about thirty-five.

There are two of them because I wanted them to represent opposite ends of a society that held fast to the traditions of class and hierarchy that the English are famous for in this time. Without an army of well-trained and inexpensive servants the Earl of Montfort’s large, luxurious country house would not have been possible to maintain to the high standard it enjoyed. In the first book: Death of a Dishonorable Gentleman Mrs. Jackson is definitely Lady Montfort’s Watson. But as the series emerges this demarcation becomes more blurred as to two women form a sort of friendship within the constraints of the social positions.

- Would you tell us just enough about Death Sits Down to Dinner to whet our appetite?

It is November 2, 1913 with Lord and Lady Montfort attending the 39th birthday party of Winston Churchill, who is First Lord of the Admiralty, in the house of an old family friend Hermione Kingsley who runs a very large and prestigious charity called the Chimney Sweep Boys. After dinner the dead body of one of the guests is found in the dining room. At this time England is in the grip of spy mania and considerable anxiety about the very real possibilities of being drawn into a war with Germany and the investigation of the murder is kept hush-hush because of Churchill’s very senior position in government. Being the woman she is Lady Montfort cannot help but involve herself in her own clandestine inquiry and she sends to the country for Mrs. Jackson to join her at Montfort House in Belgravia. Lady Montfort is so well connected that she is invited everywhere: to the ballet, to the opera, to dinners and dances. It is against this sparkling and sophisticated backdrop populated with several real Edwardian characters that she and Mrs. Jackson winkle out the identity of the murderer.

- What would we be served at an Edwardian dinner?

Eight courses would be served when one was entertaining guests. If King Edward was a guest, he expected to be served with at least twelve. He also liked his dinners to be leisurely affairs and so three hours were usual for dinner. The English loved their roast mutton and beef, but the well-off usually ate French cuisine and often employed a French chef. Dinner would be served by footmen who offered food to the guests from the left side. Here is a sample menu for a very formal dinner ““it sounds like a vast amount of food but each course would be taken by guests in a “restrained” manner. I hope you like rich food!

- Orkney oysters on the half shell

- Veal consommé with leeks

- Grilled Turbot with a cream sauce

- Rolled veal breasts stuffed with foie gras and truffles

- Roast mutton or maybe roast suckling pig or a roast goose with a red-current glaze with roast potato

- An entremets of creamed spinach, asparagus and glazed endive

- Cheese soufflé

- A moulded primrose jelly (with edible flowers in it) and decorated with whipped cream ““these were exquisite affairs that were very decorative and made wonderful centrepieces

- Hot-house fruit

- Biscuit à la crème

- Your history teacher said history was simply “very old gossip”. Dish, please. What’s your favorite piece of old gossip?

So much gossip! I promise you my history teacher’s gossip was political and not racy. Upper-crust Edwardians had considerable time to devote to the leisurely art of flirtation and romantic assignation. Married women might take a lover or two after they had produced an heir and a spare, and her husband might have a mistress tucked away in Maida Vale. The country house Saturday to Monday, as Edwardians referred to a weekend, was a great opportunity for romantic liaisons BUT discretion was key! Divorce was out of the question, and there must be no letting down the side with untidy love-affairs.

Maud, Lady Cunard, wife of Sir Bache Cunard of the famous shipping line had a long love affair with Sir Thomas Beecham. One morning they were tucked up in bed together at Sir Bache’s magnificent country estate, Nevill Holt, when the closed bedroom curtains blew aside in the wind and an estate worker who was working on the roof saw them. He must have shimmied down that ladder at top speed in order to catch a train to London so he could sell the story to the newspapers. But not quite quickly enough; he was bought off by Sir Bache who most certainly did not want his wife’s love affair broadcast to the world. Country house shenanigans was a fashion set by dear old “Bertie” (King Edward VII) who slept with all of his compliant male friend’s wives if he found them attractive. Hence the witticism: Greater love hath no man than to lay down his wife for his king.

On that racy note, we’ll end today’s interview. Stop by tomorrow for the second part of the interview with Tessa Arlen. If you’re intrigued, you might want to plan now to attend the Afternoon Tea at the Poisoned Pen on Wednesday, April 6 at 2 PM.