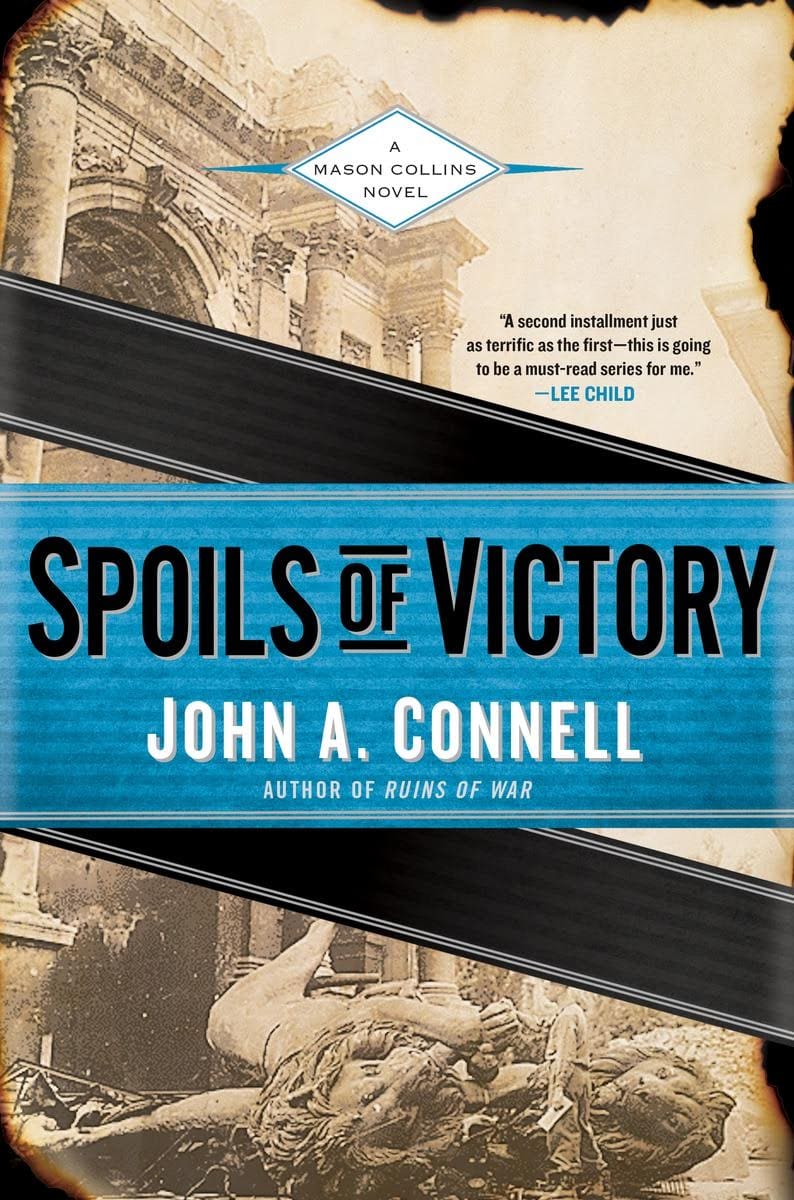

John A. Connell will be appearing at the Poisoned Pen on Wednesday, March 30 at 7 PM. The author of Spoils of Victory will join Philip Kerr as both men discuss their post-World War II crime novels.

I recently had the chance to put Connell in the hot seat, asking him ten questions. His answers were so good that we’re breaking the Q&A into two parts. Today is part 1.

- You took a circuitous route to become a writer. How did you get there?

I wrote short stories starting in my teens, mostly hybrid versions of H. G. Wells’ short stories. The first story anyone read was my history teacher in the 10th grade. I had written a gory account of the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre, and after reading it he suggested that I should become a novelist! But at that age I had dreams of being a rock-n-roll star. Music in my teens and twenties, then cinematography, occupied my creative life. Still, that bug to write was always with me, and then, around the age of 40, I expressed my dream of writing to a screenwriter friend, and he said, “Shut up, sit down, and write.” I did, and the writing “disease” immediately took hold. I started with screenplays, which seemed like the natural thing to do since I worked in the film business. But I became frustrated with the confinement of the screenplay form. I wanted to go deeper into my characters and the world that surrounded them. That’s when I tried my hand at novels and never looked back. Four previous, unpublished novels and a million words later, Ruins of War was born.

- Why are you writing about post-World War II Germany?

I’ve been a WW2 buff since I was a kid. I’ve read tons of books about the strategies, the politics, the rise and fall of Nazi Germany, though it’s the personal accounts of the individual soldiers that are my favorites. I felt I knew a good deal about the years leading up to and during the war, but I had neglected one vital part of that turbulent era: its aftermath. My previous notions of relative order were turned upside down while I was researching the backstory of the antagonist in an earlier, now defunct, novel.

The Germans called the time just after the war Die Stunde Null, “˜The Zero Hour.’ Germany had been bombed back to the Middle Ages. Death by famine, disease and murder had replaced the bullets and bombs. Every major city and many towns and villages had sustained up to 90% damage. The entire infrastructure ““ railroads, bridges and industry ““ had been damaged or destroyed. Up to 10% of the population had perished. Close to 10 million Displaced Persons—the people brought into Germany from every conquered country to work as domestic, agricultural or industrial slaves—along with the tens of thousands of POW and concentration camp survivors were all suddenly freed and making the difficult trek home or wandering the countryside. Then came the millions of ethnic Germans expelled from Poland and the former Czechoslovakia, streaming into Germany with nothing but what they could carry and in urgent need of already scarce supplies of food and shelter. The conquering armies, the Americans, British, French and Russians, wielded ultimate power over a humbled and desperate population, and a typical soldier could barter for almost anything with a single pack of cigarettes. The black market thrived, and gangs of deserted allied soldiers, former POWs and corrupt DPs (displaced persons) roamed the countryside.

SPOILS OF VICTORY takes place in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, a picturesque town in the Bavarian Alps, with gingerbread houses on Hansel-and-Gretel lanes. But the charming facades belied what Garmisch had become those first two years after the war: the Dodge City of occupied Germany. As the Third Reich collapsed, Garmisch became the stem of the funnel for fleeing wealthy Germans and Nazi war criminals, the final depository of the Nazis’ stolen art masterpieces, gold reserves, penicillin, diamonds, uranium from the failed atomic bomb experiments, all now available for purchase on the black market. With millions of dollars to be made, murder, extortion, bribes and corruption became the norm. Add into this volatile brew, tens of thousands of bored US Army soldiers ripe for temptation, and a typical soldier could barter for almost anything with a single pack of cigarettes. The black market thrived, and gangs of deserted allied soldiers, former POWs and corrupt displaced persons roamed the countryside. Talk about fertile ground for a crime thriller!

- What do you want readers to know about your hero, Mason Collins?

Actually, Mason Collins was a villain in a previous novel (may it rest in peace on my hard drive), but I found him so compelling that I decided to make him my hero in a new novel. Despite Mason’s new status as the protagonist, I wanted him to have the potential to cross over to the dark side, to borrow a well-known phrase, which is only kept in check by a strict moral code.

Early in his detective career with the Chicago Police, Mason tries to bust a ring of corrupt cops who murdered his partner. He broke the blue code of silence by going to the district attorney, but the system turned on him, framing him for selling drugs and booting him off the force. That unjust treatment fosters Mason’s distrust and lack of respect for authority. And the experience of being a POW and interned for a short time in Buchenwald has left him bitter and disillusioned with humanity. Yet, despite those deep scars, he manages to maintain his need to right wrongs, even if it means putting himself in harm’s way.

Those two elements relentlessly weigh on Mason’s psyche, threatening to push him over the line, creating a constant clash against his values of right and wrong, his sense of justice. Mason fights the temptation to give in to those impulses, taking on life one step at a time, all the while knowing that one or two steps in the wrong direction could lead him on a very dark path. One thing I would like to explore is having him turn dark at some point in the journey, something that pushes him over the edge, and then see if he can get back again.

Finally, Ruins of War and SPOILS OF VICTORY are kind of the origin story for Mason’s future wanderings. Except for his grandmother, Mason has no family to go back to, nothing to anchor him, little to create a sense of identity except through his own convictions. He becomes like a wandering samurai, masterless, homeless, and always short of cash. In fact, Toshiro Mifune’s character in the films Yojimbo and Sanjuro were inspirations for Mason’s journey—the wandering samurai, irascible and stoic, who gets deep into trouble because of his compassion and sense of justice.

- What are you reading now? What authors influenced you?

Right now, I’m reading The Highway by C. J. Box. And I can’t wait to get my hands on Philip Kerr’s latest, The Other Side of Silence!

For my influences, they start way back to my early reading experiences, anything H. G. Wells, Jules Verne, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories as a teenager. My first foray into crime fiction was Agatha Christie, followed by Dashiell Hammett, James M. Cain, and Raymond Chandler. I have so many favorite authors, crime fiction and otherwise, and scores of great works have had an influence on my writing. I can say that some of the authors who influenced my approach to Ruin of War and SPOILS OF VICTORY were James Ellroy, Dennis Lehane, Nelson DeMille, Harlan Coben, not to mention Philip Kerr, and, finally, a dash of Graham Greene.

- You’ve worked as a cameraman in film and TV. What shows have influenced your writing?

The projects that have inspired me the most were the TV shows I’ve worked on: Picket Fences and The Practice by David E. Kelley, and the most influential of all, NYPD Blue. David Milch, the creator of NYPD Blue, was a significant inspiration. He was often unsatisfied with what we had just filmed, so he would break the crew and proceed to “re-write” the scene in his head. He would then wander around the empty set, analyzing a character, or dictating new action and lines of dialogue to the script supervisor. I always elected to stay on the set during those times and watch him work, and what he came up with in those spur-of-the-moment sessions always made the scene and dialogue much more powerful.

There was also executive producer of NYPD Blue, Bill Clark. He was a retired NYPD police detective and often talked to the actors about his time on the force, what really happened behind the closed doors in interrogation rooms, or the peculiar symbiotic relationships that could develop between cop and criminal. This concept of the cop/criminal relationship intrigued me so much that I just had to include it whenever I could in my stories. I learned a lot about that world just listening to Mr. Clark’s candid remarks.

*****

Today, the questions were about John A. Connell’s background and his books, Ruins of War, and Spoils of Victory. Wait until tomorrow when we get into some personal questions! You’ll want to read how his wife describes him!